Klute (1971): Jane Fonda, Paranoia, and the Light in the Shadows

In 1971, Hollywood was changing.

The old Production Code was gone. The MPAA rating system had taken its place. Filmmakers were finally free to explore adult themes without pretending those themes didn’t exist. The result was a wave of films that felt looser, riskier, and more psychologically honest.

One of those films was Klute.

Directed by Alan J. Pakula and starring Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland, Klute is often remembered as a detective thriller. But that description misses what makes it powerful. The mystery at the center of the film is almost secondary.

This isn’t really Klute’s story.

It’s Bree Daniels’.

The Film That Changed Jane Fonda’s Career

Before Klute, Jane Fonda was known more for glamour than gravity. Roles like Barbarella cemented her as a pop culture icon — stylish, striking, and very much of the 1960s.

But Klute marked a shift.

As Bree Daniels, a New York call girl connected to the disappearance of a businessman, Fonda delivers a performance that is intimate, restrained, and emotionally layered. It earned her the Academy Award for Best Actress — and more importantly, it reframed how audiences saw her.

Bree is not written as a stereotype. She’s not a tragic victim. She’s not moralized. She’s not punished for her profession in the way earlier films might have demanded.

Instead, she’s complicated.

We see what she does — the negotiations, the performance, the practiced seduction. But in her therapy sessions, we hear what she thinks. Those sessions become the emotional spine of the film. Bree admits she doesn’t like what she does. She’d rather be an actress. And yet, ironically, she’s most convincing when she’s “acting” for clients.

That tension — between performance and identity — makes her one of the most interesting characters in early 1970s cinema.

The Shadows of Gordon Willis

If Jane Fonda gives Klute its emotional depth, cinematographer Gordon Willis gives it its atmosphere.

Willis, later known as the “Prince of Darkness,” would go on to shoot The Parallax View (1974) and All the President’s Men (1976), completing Pakula’s unofficial paranoia trilogy. But the aesthetic language begins here.

Shadows dominate Bree’s apartment. Light often falls unevenly across her face. She’s framed from above, from a distance, sometimes through architectural barriers. The camera observes her — and in doing so, implicates us in the voyeurism that defines her world.

When John Klute enters her life, the lighting subtly shifts. Lamps are turned on. Spaces brighten. It’s not heavy-handed, but it’s deliberate.

Klute represents something Bree doesn’t expect: stability. Maybe even safety.

By the end of the film, when her apartment stands empty and the phone rings unanswered one final time, the visual language has done most of the storytelling for us. The transformation isn’t announced. It’s felt.

The Investigation That Isn’t the Point

On paper, Klute is a missing persons case.

Tom Gruneman disappears. A series of explicit letters connect him to Bree Daniels. Klute, a private investigator and friend of the missing man, is hired to look into it.

The mystery unfolds in procedural fashion — interviews, surveillance, financial trails. But Pakula doesn’t spend much energy disguising the culprit. About halfway through, attentive viewers can reasonably deduce where the story is heading.

And that’s okay.

Because the investigation is not the engine of suspense.

The real tension lies in Bree’s vulnerability — and in the unsettling realization that someone has been watching her, recording her, studying her movements. Surveillance, voyeurism, paranoia — themes Pakula would explore more overtly in The Parallax View and All the President’s Men — are already present here.

The “whodunit” is almost incidental.

What matters is how Bree responds when her carefully controlled world begins to collapse.

The End of Moral Punishment

One of the most striking elements of Klute is what it doesn’t do.

Under the old Hollywood Production Code, a character like Bree would almost certainly have been punished. Crime could not pay. Immorality could not stand. Sex work would demand tragic consequences.

But the 1970s were different.

With the introduction of the MPAA rating system in 1968, filmmakers gained freedom to explore adult realities without embedding moral lectures. Klute portrays sex work directly and frankly. The dialogue is open. The transactions are explicit. And yet, Bree is treated as a full human being, not a cautionary tale.

The film doesn’t glorify her life.

But it doesn’t condemn her either.

That balance is part of what made the role groundbreaking — and part of why Fonda’s Oscar felt earned.

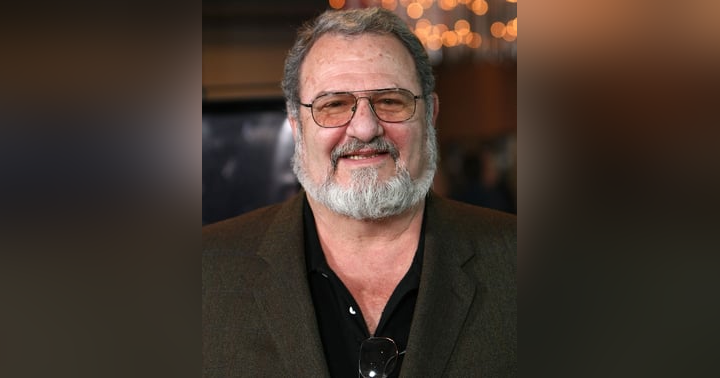

Donald Sutherland’s Understated Klute

It’s worth noting that the film bears his name.

Donald Sutherland plays John Klute as quiet, steady, almost reserved to a fault. This was not the flamboyant energy of MASH* or the swagger of a classic hard-boiled detective. Klute is competent, observant, and uncomfortable with the moral gray areas he must navigate.

He surveils Bree — but he doesn’t enjoy it.

He investigates — but he doesn’t grandstand.

That restraint makes his presence effective. He becomes the steady counterweight to Bree’s volatility.

And yet, despite the title, the film ultimately belongs to her.

So… Did It Groove?

Klute is not a perfect thriller. The mystery is thin. The climax lacks some urgency. The resolution edges toward optimism in a way that feels almost tentative.

But as a character study — and as a marker of where 1970s American cinema was heading — it absolutely grooves.

Jane Fonda’s performance is layered and controlled. Gordon Willis’ cinematography quietly reinforces the film’s psychological themes. And Alan J. Pakula begins exploring the paranoia that would define some of the decade’s most enduring political films.

It may be titled Klute.

But it’s Bree Daniels who lingers long after the credits roll.